If I had to choose a single desert island art tool, I'd go with a pencil. Nothing can touch it for versatility, economy and simplicity. You can suggest sharp ink lines, soft charcoal strokes and watercolor washes, all with this extremely cheap and available instrument. In fact, pencils are so cheap and available that it's easy to forget just how ingenious they are.

Prior to the mid-1500s, graphite drawing sticks were wrapped in sheepskin or string to keep them from breaking. It wasn't until the 1560s that wood was used to encase the lead by taking two carved halves and gluing them together. The first attached eraser didn't happen until 1858. Actually, there is no real lead in pencils, it's graphite. The material was misidentified by early chemists. Contrary to what you may have heard as a kid, the graphite "lead" is harmless if you accidentally swallow it. There used to be a danger of lead poisoning, but that came from chewing or sucking on the outside of the pencil. Until the 1950's, the paint used on the outer casing often contained lead.

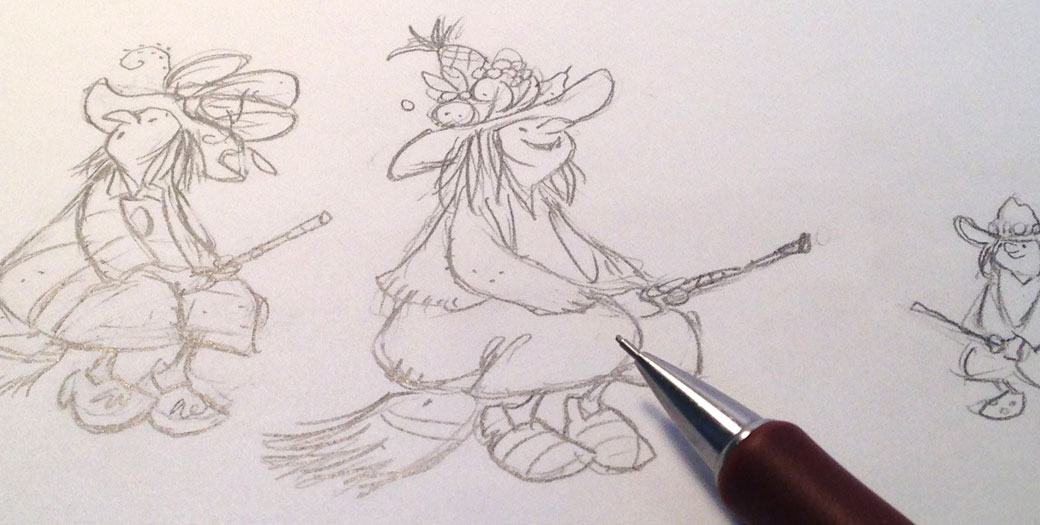

The production flow and rendering tools for each of the books I've illustrated has varied, but they've all started with a pencil. For general sketching and storyboarding I've discovered that I actually prefer a mechanical pencil to a wooden pencil. A semi-soft HB or F grade lead allows a nice balance of line control and texture for the smallish scale that I tend to draw in - usually at actual size or smaller. Wooden pencils are great for a lot of things, but the tip does wear down comparatively quickly and the uneven line width can be frustrating when I'm doing detail work. I still use the flat of the wood pencil lead for shading sometimes, but I prefer the consistent tip of the mechanical pencil for most drawing. I use a $5 Pentel Twist-Erase, usually with a 0.7 tip.

The very nature of the pencil line suggests impermanence, which is a good creative mindset to try to get into when I'm trying to sculpt a scribble into shape. My first scribbles are often distorted funhouse mirror versions of what I'm trying to extract - but they're a start. "Kill all your darlings" Faulkner once famously advised young writers, and I feel the same way about concept art. Sketch, erase, sketch, erase. Even as the drawing starts to take shape I'll erase various parts or completely re-draw it again just so I can come at it from a slightly different angle. New iterations allow a greater understanding of the subject. I always try to push a drawing until it clicks. And that can mean a lot of drawing and erasing.

Somehow I discovered that marker paper (of all things) is a really versatile surface for pencil work. It's not really made for pencils, but it does a couple of things really well that I find extremely valuable: the surface stays smooth even after being erased many times, and it's transparent enough for tracing. My go-to brand is Bienfang's Graphics 360 100% Rag Translucent Marker Paper. It's thicker than tracing paper but thinner than drafting vellum. The only downside is that the smooth surface doesn't hold graphite as well as traditional drawing paper so it smudges pretty easily. As I draw I have to be careful not to slide the side of my hand across the work.

A pencil gives the most immediate visual voice to the ideas rattling around in my head. Even a very rough sketch can usually do a better job of communicating my ideas to an editor or client than I can describe with words. And anything that gets us on the same page early on can save a lot of time and trouble down the line.

SH